A network is a communication system that helps computers interact with each other. To enable this interaction, certain rules must be followed. These rules are known as protocol. A protocol is nothing but a set of rules or formats that are followed to create a means of effective communication between two or more computers. It is very difficult to build a protocol that is sufficient to cater to various kinds of applications and computers. Therefore, the need for a common platform that supports protocols at various levels of communication arises. Such a platform is the OSI reference model.

blog.urfix.com will discuss the different layers of the OSI reference model.

You will also learn in greater detail about the important layers of network security.

Open Systems Interconnection (OSI)

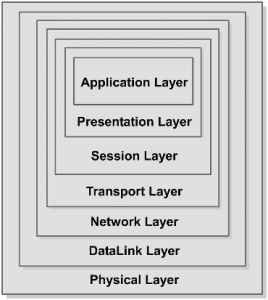

The OSI reference model is an open set of definitions that presents a common technical framework for standardization of communication. This framework provides an infrastructure that is sufficient to place mandatory and optional components of effective communication in place. The OSI reference model is divided into several layers. Each layer provides a plug-in space to various components involved in networking. The layers of the OSI reference model are illustrated below.

The layers of the OSI reference model are as follows:

- Physical layer

- DataLink layer

- Network layer

- Transport layer

- Session layer

- Presentation layer

- Application layer

Let urfix.com explain each of these layers

Physical Layer

The physical layer is essentially the hardware support layer for networking equip-

ment. This layer provides electrical and functional characteristics to initialize,

maintain, and deactivate physical network links. Network links send bit streams

of data and understand information only in the form of individual bits. The

cabling used in a network is an example of a component that operates in the phys-

ical layer of the OSI model.

The physical layer takes care of the following components in a network:

- Transmission medium

- Means of signaling

- Timing and clocks

- Synchronous serial communication

Network security is not limited to intrusions; it also involves choosing the right

type of hardware while setting up your network. Therefore, though the physical

layer might not seem to be a very important part in a secure network, you can’t

overlook it. For example, poor quality cabling might save initial infrastructure

costs, but in the long run, it can lead to data loss even in the best protocols, such

as the User Datagram Protocol (UDP), and cause severe network performance

problems with other reliable protocols. Therefore, you should always use stan-

dardized networking equipment and avoid bizarre configurations for your net-

work—even if investing in standard networking components pushes the

networking budget a little higher.

Data Link Layer

The data link layer is the second basic layer of the OSI model. It provides a func-

tional and procedural medium for the exchange of data between network entities.

This layer understands data in the form of characters and enables you to initialize

and maintain data link connections. An example of a component that functions in

this layer of the OSI model is the standard of the Institute of Electrical and Elec-

tronic Engineers (IEEE), the IEEE 802.3 or Ethernet. Ethernet is a widely

accepted standard for LAN, and it can accommodate up to 1024 nodes. If the

distance is greater, the High-Level Data Link Control (HDLC)-based networks

are used.

Network Layer

The network layer is an important layer from the point of view of a network

administrator. This layer encapsulates most upper layers of the OSI model and

provides point-to-point interaction between the two networking components in

the upper layer. Some components of this layer, such as IP, Routers, and ICMP,

are important for network security. These components are discussed in the fol-

lowing sections.

Internet Protocol

Internet Protocol (IP) operates in the third layer of the OSI model and provides

encapsulation facilities to protocols that operate in the higher levels of the model.

An example of this is shown below.

The IP protocol uses datagrams to communicate over a packet-switched network.

In a packet-switched network, every packet of data that is traveling through a

network is treated as a separate entity. The packet contains a header information

section, which contains the address of the recipient, and other important details

about the data within the packet. Intermediate systems, such as routers (discussed

in the next section) use this header information to forward the packet to the cor-

rect path or return an error message if the packet cannot be forwarded. An IP

datagram is depicted below.

Following is the structure of the IP packet header:

- Version. This is the version of the IP.

- IP Header Length. This field contains the size of the IP header. Note

that this field contains only the length of the IP header and not the

combined length of all headers that may be encapsulated inside the

IP packet. - Type of Service. This field is usually set to zero and defines the “quality”

of service that is expected from a network. - Packet Size. This field contains the total size of the packet, which is the

sum of the size of the header and the size of actual data. - Identification. This is a 2-byte number that is used by recipient comput-

ers to arrange fragmented data packets before merging them. More

information on packet fragmenting and merging can be found in the

“Routers” section of this chapter. - Flags. This is a combination of three bits that inform the intermediate

systems about the fragmenting feasibility for a packet. The field also

contains the Don’t Fragment (DF) flag of the IP packet. - Fragmentation Offset. This is a 13-bit byte count that starts from the

first byte of the original packet (the packet before any fragmentation).

This counter helps the end system, or the recipient computer, to confirm

correct re-assembly of the packet. - Time To Live. This field contains an 8-bit number of hops that a packet

can sustain. A packet can be routed only up to a certain number of times,

which is specified in this field. This is done to avoid a scenario in which a

packet continues to hop infinitely inside a network. Every time a packet

is passed through a network, this number is decremented by the router. - Protocol. This field specifies the type of packet that is encapsulated

inside the IP packet. A specific number represents each higher level,

encapsulated protocol type. For example, if the packet being carried is an

ICMP packet, the value of this field is 1. Similarly, if the packet is a

TCP packet, the value of this field is 6. - Header Checksum. This field is a checksum number that can inform the

recipient or an intermediate system whether the IP header is corrupted.

End recipients or intermediate systems discard packets if the checksums

are wrong. The checksum is initially inserted by the sender of the packet

and can be updated by every intermediate system if any changes (such as

fragmentation) are made to the packet. - Source Address. This is the IP address of the original sender of the

packet. This field can be dangerously modified to spoof the identity of

the sender during a network attack. - Destination Address. This is the IP address of the final recipient of the

IP packet. - Options. The options are almost never used. If they are used, however,

the size of the IP header can be increased.

Routers

Routers are computers or gadgets that do not directly store usernames or act as a

server or a client. Routers operate at the Network Layer 3 (L3) of the OSI model.

They forward data to the intended recipient. Routers may be used to connect two or more IP networks or to connect an IP network to an Internet connection.

Although routers need not know the information being sent through them, they

might modify certain aspects of the information to enable information packets to

reach the correct destination.

A router, in physical terms, consists of a computer with a minimum of two net-

work interface cards. Both these network cards should support IP. A router

receives a packet from each interface and forwards the received packets to an

appropriate output network interface. All packets received by the router have

DataLink layer (L2) protocol headers. The router removes these headers and adds

a new DataLink Layer header to the packet. After the new header is added to the

packet, it can be transmitted using the appropriate network interface.

A router reads the network layer header or IP header information before it can

decide the following:

- Should the packet be forwarded?

- Which network interface should the packet be forwarded to?

A series of steps is involved in routing a packet. These steps are shown here:

1. The router receives a packet.

2. The packet’s header information is extracted.

3. The destination IP address of the packet is extracted.

4. If the size of the packet is larger than the Maximum Transfer Unit

(MTU) and the packet’s header information has a Don’t Fragment (DF)

flag set, the packet is discarded. A message of failure is sent to the origi-

nal sender of the packet.

5. If the size of the packet is larger than the MTU but the DF flag is not

set, the packet is broken down into smaller fragments.

6. The best path for the packet is found by searching the routing table

stored inside the router.

7. If the size of the original packet is larger than the MTU, the small frag-

ments are dispatched through the appropriate network interface. Other-

wise, the packet is forwarded to its destination address.

8. The packet fragments are collected at the destination and reassembled.

Routing tables have the same format as the tables in network bridges

and switches. The difference is that routers are identified by the IP addresses of

computers instead of MAC hardware addresses.

The routing table is nothing but a list of known IP destination addresses and the

associated network interfaces that can be used to reach the destinations. Routers

also have a provision for a default network interface. This interface may be used

for all addresses that are not mentioned in a routing table. Routers also provide

packet filters. The packet filter simply discards unwanted packets, which can

cause an unnecessary overload on networks. The filter can be used as a firewall,

and unsupported protocols can be blocked outside the router. Such a firewall, to

some extent, can provide basic security to prevent unauthorized users from enter-

ing a network using remote computers.

The basic purpose of a router is to forward packets from one IP network to

another IP network. A router determines the broadcast IP destination of a net-

work from the logical AND of an IP address and its associated subnet mask. If a

router isn’t configured properly, a serious security threat can occur when a packet

is sent to a network broadcast address. If a large number of packets is forwarded,

your network might face the problem of network overload.

Routers are often used to connect different types of networks. A router can connect networks that use totally different link methodologies. For example, an HDLC link can connect a WAN to an Ethernet-based LAN, as shown below

The important thing to note here is that each of these networks has a different

MTU. This is due to the fact that optimization levels for packet sizes are differ-

ent for the two networks. Therefore, whenever a packet comes from the network

that has a bigger MTU and needs to go to the network with a smaller MTU

Transport Layer

The fourth layer in the OSI reference model is the transport layer. This layer facil-

itates data transfer between two end systems by encapsulating the data packet

within the network layer data packet. Two important components of the transport

layer are TCP and the UDP protocol, which are discussed in detail in this section.

TCP is a connection-oriented and reliable transport protocol. A connection-ori-

ented protocol implies that two hosts, wanting to communicate with each other,

must first establish a connection before actual data exchange can take place. In

TCP, a connection is established using a three-way handshake. TCP assigns

sequence numbers to every packet in each segment, and all data received is

responded to with an acknowledgement to the sender. TCP hides perplexing net-

work details from the upper layers of the IP protocol.

Information Fields in a TCP Packet

A typical TCP packet contains the following six information fields along with

actual data:

- Synchronize Sequence Numbers (SYN). This field is valid only during

the three steps involving the handshake. The sequence number is read by

the receiving host and is stored as the client computer’s first sequence

number. TCP sequence numbers are 32-bit numbers, ranging from 0 to

4,294,967,295(2 ^ 32). Every packet of data that is exchanged between

two computers using a TCP connection is sequenced. - Acknowledgement (ACK). This field is generally set. The acknowledge-

ment number field in the TCP header contains the assumed value of the

next sequence number. This field is also an acknowledgement of the data

received in the previous packet. - Reset (RST). This field informs the other computer that the connection

has been dropped and all memory structures have been flushed. - Urgent (URG). This field informs the other computer to process data on

a priority basis. - Push (PSH). This field informs the other computer to pass the data to

the concerned application as soon as possible instead of putting the data

in the queue. This flag is generally set in interactive connections, such as

Telnet, rlogin, and some chat applications. - Finish (FIN). This field informs the other computer that the transmis-

sion of data is complete, but the host is still open to accepting data.

User Datagram Protocol (UDP)

The US Department of Defense (DoD) developed UDP for use with IP. Unlike

TCP, which first tries to establish a reliable connection with the server, UDP

works on the concept of “best-effort mechanism.” However, UDP is an unreliable

protocol for communication because of the following reasons:

1. No error is generated for lost data packets.

2. No error is generated for duplicate packets.

3. No assurance is provided that a packet has reached the destination safely.

In simpler terms, UDP is a one-way protocol—what is sent from the client

is gone for good. The client will never hear any further information about this

packet.

Although some reliability is provided in UDP, the end recipients reject packets

that are corrupted during transit. It’s the responsibility of the upper layer applica-

tion to check such loss. In addition, because no packet acknowledgement is

required in UDP, the network load is reduced to a certain extent.

The UDP header consists of four fields, each two bytes in length:

- Source Port

- Destination Port

- UDP Data Length

- UDP Checksum

UDP is unsuitable for many applications, although the simplicity of the protocol

gives performance advantage to those applications that do not require much reli-

ability. An example of such an application is one that pertains to streaming video

and audio content.

What Are Ports?

Port is a term that is used often in networking. Regardless of whether your computer is online or offline, your computer has a number of open channels to which various programs or other computers can connect. These channels are known as ports. Obviously, if your computer isn’t connected to a network, only the local program will be able to access these ports. Once a computer is online, however, anyone on the network can execute a client program on their remote computer to connect to these ports. Ports are channels created between two computers for the exchange of information. A computer can have many open ports for receiving connection requests. For example, a server that has SSH, HTTP, SMTP, POP, FTP, and Telnet services can have five open ports. The default port numbers of SSH, HTTP, SMTP, POP, FTP, and Telnet are 22, 80, 25, 110, 21, and 23, respectively. These ports are not hardware components, but are like virtual stations within your computer’s memory. All computers have them, including the server you dial to access the Internet. When a computer is turned on, a number of ports are virtually created. These remain open and search for programs that are running on remote or local computers. This process is known as listening. If another computer wishes to connect to a port on your computer, it can do this in two ways: by being offered a port address to connect to, or by scanning available open ports. Sometimes, your computer willingly gives a port number to another computer to make a connection. At other times, the other computer might just guess or try one of the universally known port numbers. However, hackers might also choose to run a port scan through your computer from a remote location. A port scanner is software that allows a user to search all ports that a server is listening to. When such a program is used, the user simply has to type the IP address of the desired computer, and the scanner presents a complete report of all ports that are being listened to by the host computer.

Session Layer and Presentation Layer

The session layer is the fifth layer in the OSI model, and it offers a channel to ses-

sion-based services, such as:

- Telnet. Telnet is a protocol that can be used to perform remote logins

and operate a remote computer from a virtual terminal. - FTP. FTP is used for transferring files between two connected

computers.

Both these protocols maintain user sessions from the time they log on to the time

they log out. The session layer supports a feature that helps in structuring response

dialogues between computers. This feature allows two-way simultaneous or alter-

native cross-network operations.

The presentation layer supports a common syntax and provides conversion facili-

ties from one type of network to another. This layer also permits computers to be

referenced by their names, rather than by their difficult-to-remember addresses.

The presentation layer defines how applications should use a network. An exam-

ple of a component that operates in this layer is the SMB protocol. The SMB pro-

tocol provides naming facilities and file sharing features in Windows and

UNIX-based networks, using appropriate servers.

Application Layer

The application layer is the uppermost layer in the OSI model. This layer is used

directly by applications. Data belonging to this layer cannot generally travel in a

network on its own and requires encapsulation by another layer to reach the destination.

The application layer can be considered the cause of the existence of all other layers of the OSI model. The other layers in the OSI model carry the application

layer data. All services in a server send application layer data packets. Similarly, all client programs exchange data using this protocol. This layer does all the actual work and is supported by the other layers. Some programs that operate in this layer are

- E-mail servers and clients, such as sendmail

- Web servers and clients, such as Apache

- DNS servers, such as Bind

Summary

You learned about the different layers of the OSI model and their

roles in a network. I discussed the data link, network, transport,

session, presentation, and application layers of the OSI reference model.

UrFix knows you will find these basic fundamentals in all networking technologies that use

the Internet.